|

|

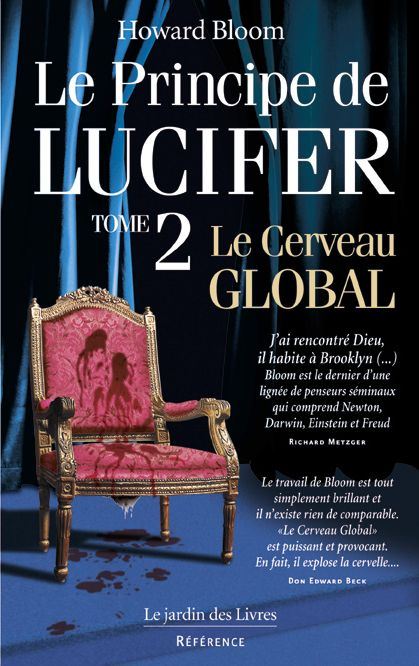

HRM-BULULU2 24,90 €

151 Lee Alan Dugatkin. « Interface between Culturally Based Preferences and Genetic Preferences: Female Mate Choice in Poecilia Reticulata ». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2 avril 1996, pages 2770-2773.

152 Keven N. Laland et Kerry Williams. « Social Transmission of Maladaptive Information in the Guppy ». Behavioral Ecology, septembre 1998 ; Stephanie E. Briggs, Jean-Guy Godin, J. Dugatkin et Lee Alan. « Mate-Choice Copying under Predation Risk in the Trinidadian Guppy (Poecilia Reticulata) ». Behavioral Ecology, été 1996 ; A. Kodric-Brown et P. F. Nicoletto. « Consensus among Females in Their Choice of Males in the Guppy Poecilia Reticulata » Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 39:6 (1996) ; Constance Holden. « Nature v. Culture: A Lesson from the Guppy ». Science, 12 avril 1996, page 203.

153 W. F. Herrnkind. « Evolution and Mechanisms of Mass Single-File Migration in Spiny Lobster ». Migration: Mechanisms and Adaptative Significance. Contributions in Marine Science - Monographic Series, vol. 68. Austin : Marine Science Institute, University of Texas -Austin, 1985, pages 197-211.

154 P. Bushmann et J. Atema. « Aggression-Reducing Courtship Signals in the Lobster, Homarus Americanus ». Biological Bulletin, octobre 1994, pages 275-276 ; Christa Karavanich et Jelle Atema. « Individual Recognition and Memory in Lobster Dominance ». Animal Behaviour, décembre 1998, pages 1553-1560 ; Paul J. Bushmann et Jelle Atema. « Shelter Sharing and Chemical Courtship Signals in the Lobster, Homarus Americanus ». Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science, mars 1997 ; Christa Karavanich et Jelle Atema. « Olfactory Recognition of Urine Signals in Dominance Fights between Male Lobster, Homarus Americanus ». Behaviour, septembre 1998 ; Elise B Karnofsky, Jelle Atema et Randall H. Elgin. « Field Observations of Social Behavior, Shelter Use, and Foraging in the Lobster, Homarus Americanus ». The Biological Bulletin, juin 1989 ; Elisa B. Karnofsky, Jelle Atema et Randall H. Elgin. « Natural Dynamics of Population Structure and Habitat Use of the Lobster, Homarus Americanus, in a Shallow Cove ». The Biological Bulletin, juin 1989 ; Wallace Ravven. « Lobster Lust: Don Juans of the Deep ». Discover, décembre 1987, pages 34-40.

155 Oui, cette même sérotonine que l'on retrouve dans les anti-dépresseurs type Prozac ou Zoloft et qui « booste » le cerveau.

156 Marcia Barinaga. « Social Status Sculpts Activity of Crayfish Neurons ». Science, 19 janvier 1996, pages 290-291 ; Shih-Rung Yeh, Russell Fricke et Donald Edwards. « The Effect of Social Experience on Serotonergic Modulation of the Escape Circuit of Crayfish ». Science, 19 janvier 1996, pages 366-369 ; Justine H. Lange. « Dominance in Crayfish ». Science, 5 avril 1996, page 18 ; Shih-Rung Yeh, Barbara E. Musolf et Donald H. Edwards. « Neuronal Adaptations to Changes in the Social Dominance Status of Crayfish ». Journal of Neuroscience, janvier 1997, pages 697-708 ; T. Nagayama, H. Aonuma et P. L. Newland. « Convergent Chemical and Electric Synaptic Inputs from Proprioceptive Afferents onto an Identified Intersegmental Interneuron in the Crayfish ». Journal of Neurobiology, mai 1997, pages 2826-2830.

157 Alisdair Daws. Communication personnelle. 11 avril 1999.

158 Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies. Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 1971, page 4. Répété dans Bert Holldobler et Edward O. Wilson. The Ants. Cambridge, Massachusetts : Belknap Press, 1990, pages 27-28.

159 Kerry B. Clark. Correspondance personnelle. 27 mars 1997.

160 Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, page 439.

161 Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, page 4. Répété dans Bert Holldobler et Edward O. Wilson. The Ants, pages 27-28.

162 Wilson indique clairement que le fameux entomologiste William Morton Wheeler se basait déjà sur la présomption selon laquelle l'état de solitude était le prédécesseur évolutionniste de la socialité lorsque Wheeler publia Social Life among the Insects en 1923. (Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, page 120)

163 Conrad C. Labandeira et Tom L. Phillips. « Trunk Borings and Rhachis Skulls of Tree Ferns from the Late Pennsylvanian (Kasimovian) of Illinois; Implications for the Origin of the Galling Functional Feeding Group and Holometabolous Insects ». Paleontographica, partie A (à l'impression) ; Conrad C. Labandeira. Communication personnelle. 16 février 1999 ; Christine Nalepa. Communication personnelle. 6 avril 1997.

164 Stephen T. Hasiotis, Russell F. Dubiel, Paul T. Kay, Timothy M. Demko, Krystyna Kowalska et Douglas McDaniel. « Research Update on Hymenopteran Nests and Cocoons, Upper Triassic Chinle Formation, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona ». National Park Service Paleontological Research, janvier 1998, pages 116-121.

* « Une colonie d'esprit : la ruche en tant que machine pensante ». (NdT)

165 Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, page 273.

166 Karl von Frisch. The Dance Language and Orientation of Bees, traduit par Leigh E. Chadwick. Cambridge, Massachusetts : Belknap Press, 1967, page 17. Cette expérience a depuis été reproduite de manière informelle par James L. Gould de la Princeton University, qui a pu observer un grand nombre de détails supplémentaires de ce phénomène. (James L. Gould. Communication personnelle. Avril 1997)

167 La « disposition » de l'esprit d'une abeille qui transforme un insecte en module d'une machine à calculer capable de dresser une carte géographique avec une telle précision est décrite dans L. A. Real. « Animal Choice Behavior and the Evolution of Cognitive Architecture ». Science, 30 août 1991, pages 980-986. Voir également : P. K. Visscher. « Collective Decisions and Cognition in Bees ». Nature, 4 février 1999, page 400.

168 Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, page 265.

169 Karl von Frisch. Bees: Their Vision, Chemical Senses, and Language. Ithaca, New York : Cornell University Press, 1950, pages 53-96 ; Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, pages 267-271 ; Thomas D. Seeley. Honeybee Ecology: A Study of Adaptation in Social Life. Princeton, New Jersey : Princeton University Press, 1985, pages 83-88 Honey Bee Colonies. Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 1995, pages 36-39.

170 Thomas D. Seeley. Honeybee Ecology, page 41.

171 Ibid., pages 40-43.

172 Ibid., page 101.

173 Ibid., page 83.

174 Ibid., page 30.

175 Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, page 297.

176 Thomas D. Seeley. The Wisdom of the Hive, pages 34-36.

* En français dans le texte. (NdT)

177 Thomas D. Seeley. Honeybee Ecology, pages 71-75.

178 Bert Holldobler et Edward O. Wilson. The Ants, page 27.

179 Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, page 452.

180 Ibid., page 250.

181 J. L. Deneubourg, S. Aron, G. Goss, J. M. Pasteels et G. Duerinck. « Random Behaviour, Amplification Processes and Number of Participants: How They Contribute to the Foraging Properties of Ants ». Dans Evolution, Games and Learning: Models for Adaptation in Machines and Nature, Proceedings of the Fifth Annual International Conference of the Center for Nonlinear Studies, éd. Doyne Farmer, Alan Lapedes, Norman Packard et Burton Wendroff. Amsterdam : North-Holland Physics Publishing, 1985, page 181.

182 Edward O. Wilson. The Insect Societies, page 238.

183 R. T. Bakker. « The Dinosaur Renaissance ». Scientific American 232 (1975), pages 58-72 ; R. T. Bakker. « Ecology of the Brontosaurs ». Nature, 15 janvier 1971, pages 172-174.

184 Robert T. Bakker. Raptor Red. New York : Bantam, 1996, pages 7-217 ; Robert T. Bakker. The Dinosaur Heresis: New Theories - Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction. New York : William Morrow, 1986.

185 Lianhai Hou, Larry D. Martin, Zonghe Zhou et Alan Feduccia. « Early Adaptative Radiation of Birds: Evidence from Fossils from Northeastern China ». Science, 15 novembre 1996, pages 1164-1167.

186 Des groupes d'oiseaux anciens nommés Confuciusornis trouvés sur les rives d'un lac de la province de Liaoning, dans le nord-est de la Chine.

187 University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. « Discovery of New Bird Species in China, Oldest Beak Shows Evolution Complexity ».

www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1999/06/990617072348.html. Juin 1999.

188 C. Feare. The Starling. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1984, pages 24-67.

189 On a relevé une distance de 86 km (aller-retour pour se nourrir) chez une volée de 836 corbeaux près de Malheur Lake, dans l'Oregon. (Bernd Heinrich. Ravens in Winter. New York : Summit Books, 1989, pages 164-165)

190 E. Curio, V. Ernst et W.Vieth. « Cultural Transmission of Enemy Recognition: One Function of Mobbing ». Science 202 (1978), pages 899-901. Pour en savoir plus sur un comportement similaire chez les rats, voir : B. G. Galef Jr. et E. E. Whiskin. « Learning Socially to Eat More of One Food Than of Another ». Journal of Comparative Psychology, mars 1995, pages 99-101.

191 P. Ward et A. Zahavi. « The Importance of Certain Assemblages of Birds as 'Information-centres' for Food-Finding ». Ibis 115-4 (1973), page 517-534.

192 John Marzluff. Communication personnelle. 4 mars 1996.

193 John Marzluff. Communication personnelle. 1997 ; John Marzluff, Bernd Heinrich et Colleen S. Marzluff. « Raven Roosts Are Mobile Information Centres ». Animal Behaviour 51 (1996), pages 89-103 American Scientist, juillet-août 1995, pages 342-350 ; B. Heinrich et J. M. Marzluff, « Do Common Ravens Yell Because They Want to Attract Others? » Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 28 (1991), pages 13-21, et P. de Groot. « Information Transfer in a Socially Roosting Weaver Bird (Quelea Quelea; Ploceinae): An Experimental Study ». Animal Behaviour 28 (1980), pages 1249-1254.

194 Howard Bloom. « Beyond the Supercomputer: Social Groups as Self-Invention Machines ». Dans Sociobiology and Biopolitics, éd. Albert Somit et Steven A. Peterson. Research in Biopolitics, vol. 6. Greenwich, Connecticut : JAI Press, 1998, pages 43-64.

195 Doyne Farmer, Alan Lapedes, Norman Packard et Burton Wendroff, éd. Evolution, Games and Learning: Models for Adaptation in Machines and Nature, Proceedings of the Fifth Annual International Conference of the Center for Nonlinear Studies. Amsterdam : North-Holland Physics Publishing, 1985, page 188.

196 Des juges internes de toute sortes apparaissent dans le cerveau et le corps. Les travaux de Neil Greenberg indiquent que l'une de ces zones clés est le striatum. (Neil Greenberg, Enrique Font et Robert C. Switzer III. « The Reptilian Striatum Revisited: Studies on Anolis Lizards. » Dans The Forebrain of Reptiles: Current Concepts of Structure and Function, éd. Walter K. Schwerdtfeger et Willhelmus J. A. J. Smeets. Basel, Suisse : Karger, 1988, pages 162-177.) Le striatum peut causer de gros dégâts à des capacités primordiales, comme celle traduire la pensée par le mouvement ou celle de calmer la souffrance du stress. Greenberg met également en avant un autre juge interne, qui diminue notre sexualité. (Neil Greenberg. Communication personnelle. 20 juin 1998.)

197 Vous trouverez un exemple dans : Myron F. Floyd. « Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance: Exploring Affective Determinants of Recreation Satisfaction ». Leisure Sciences, avril-juin 1997, pages 83-96.

198 En termes de réseaux neuronaux, ces mécanismes sont dits « d'auto-inhibition ». (T. Fukai et S. Tanaka. « A Simple Neural Network Exhibiting Selective Activation of Neuronal Ensembles: From Winner-Take-All to Winners-Share-All ». Neural Computation, janvier 1997, pages 77-97).

199 B. S. McEwen. « Corticosteroids and Hippocampal Plasticity ». Brain Corticosteroid Receptors: Studies on the Mechanism, Function, and Neurotoxicity of Corticosteroid Action, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 746, 30 novembre 1994, pages 142-144 et 178-179 Glucocorticoid-Mediated Cell Death in the Hippocampus ». Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy, août 1997, pages 149-167.

200 Non seulement les juges internes endorment nos esprits en diminuant la circulation du cerveau, mais ils nous donnent aussi des maux de tête. (Roy J. Mathew et W. H. Wilson. « Intracranial and Extracranial Blood Flow during Acute Anxiety ». Psychiatry Research, 16 mai 1997, pages 93-107.)

201 R. J. Mathew, A. A. Swihart et M. L. Weinman. « Vegetative Symptoms in Anxiety and Depression ». British Journal of Psychiatry, août 1982, pages 162-165 ; Klaus Atzwanger et Alain Schmitt. « Walking Speed and Depression: Are Sad Pedestrians Slow? » Human Ethology Bulletin, 3 septembre 1997.

202 Bacillus subtilis nous aide en produisant la bacitracine antibiotique.

203 L'utilisation ironique des termes « Dogme Central » pour décrire le néo-darwinisme est une formule inventée par les auteurs du Biology Hypertextbook du MIT (« Central Dogma Directory ». Dans Experimental Study Group, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Biology Hypertextbook. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Avril 1999

http://esg-www.mit.edu:8001/esgbio/dogma/dogmadir.html.

204 O. W. Godfrey. « Directed Mutation in Streptomyces Lipmanii ». Canadian Journal of Microbiology, novembre 1974, pages 1479-1485.

205 Tom Keely. « Rethinking Darwin ». Technology Review, mai-juin 1990, pages 19-20 ; W. Stolzenburg. « Hypermutation: Evolutionary Fast Track? » Science News, 23 juin 1990, page 391 Science News, 10 mars 1990, page 149 ; Richard Lipkin. « Bacterial Chatter: How Patterns Reveal Clues about Bacteria's Chemical Communication ». Science News, 4 mars 1995, page 137 ; Richard Lipkin. « Stressed Bacteria Spawn Elegant Colonies ». Science News, 9 septembre 1995 ; G. Maenhaut-Michel et J. A. Shapiro. « The Roles of Starvation and Selective Substrates in the Emergence of araB-lacZ Fusion Clones. » EMBO Journal, 1er novembre 1994, pages 5224-5239.

* Boîtes d'expérimentation bien connues dans les laboratoires (NdT).

206 Eshel Ben-Jacob. « Bacterial Wisdom, Gödel's Theorem and Creative Genomic Webs ». Physica A 248 (1998), pages 58-59.

207 Ibid. ; J. A. Shapiro. « Natural Genetic Engineering in Evolution ». Genetica 86:1-3 (1992), pages 99-111 ; J. A. Shapiro. « Natural Genetic Engineering of the Bacterial Genome ». Current Opinion in Genetics and Development, décembre 1993, pages 845-848 ; J. A. Shapiro. « Genome Organization, Natural Genetic Engineering and Adaptative Mutation ». Trends in Genetics, 13 mars 1997, pages 98-104. Shapiro n'est pas d'accord avec Ben-Jacob qui attribue une créativité résolue et une « intelligence » à l'esprit collectif d'une colonie bactérienne. (James A. Shapiro. Communication personnelle. 9 février 1999.) Bien qu'il s'agisse là d'un désaccord entre deux géants du domaine, mes trente ans de travail sur le terrain et d'observation du comportement collectif me poussent à me ranger du côté de Ben-Jacob.

208 Selon Ben-Jacob : « Les mutations aléatoires existent bel et bien et affectent également la créativité. Néanmoins, je pense que les modifications mises au point jouent un rôle plus essentiel dans l'évolution. » Eshel Ben-Jacob. « Bacterial Wisdom, Gödel's Theorem and Creative Genomic Webs ». Physica A 248 (1998), pages 57-59.

* En français dans le texte. (NdT)

209 Pour ceux qui souhaitent vérifier l'arithmétique, voici les faits. « La souche d'Escherichia coli K12 chi 342LD nécessite deux mutations de l'opéron bgl (béta-glucosidase), bglR0--bglR+ et une excision de IS103 de l'intérieur de bglF, pour pouvoir utiliser la salicine. Dans les cellules en développement, les deux mutations se produisent à des fréquences respectives de 4x10(-8) par division cellulaire et de moins de 2x10(-12) par division cellulaire. (...) Les deux mutations se produisent par séquence (...). Il apparaît que les mutants d'excision ne sont pas avantageux aux colonies ; ils doivent donc résulter d'excisions indépendantes ultérieures, dans la vie de la colonie. L'excision de IS103 se produit uniquement sur un contenant moyen de salicine, malgré le fait que l'excision elle-même ne confère aucun avantage sélectif détectable. » En utilisant les formules standard de permutations et de combinaisons, je pense que vous trouverez que les rares chances d'évoluer spontanément dans la consommation de salicine sont bien plus grandes que le chiffre prudent donné ci-dessus.

210 Normalement, le mot « apprendre » serait scientifiquement inacceptable dans le contexte des bactéries ; néanmoins, c'est le terme qu'emploie Ben-Jacob. (Eshel Ben-Jacob. « Bacterial Wisdom, Gödel's Theorem and Creative Genomic Webs ». Physica A, page 70).

211 Ibid., page 71.

212 James A. Shapiro. « Thinking about Bacterial Populations as Multicellular Organisms » Annual Review of Microbiology. Palo Alto, Californie : Annual Reviews, 1998, pages 83-88.

213 Ibid., pages 92-93 ; Eshel Ben-Jacob. Communications personnelles. 1996 ; J. M. Solomon et A. D. Grossman. « Who's Comptetent and When: Regulation of Natural Genetic Competence in Bacteria ». Trends in Genetics 12 (1996), pages 150-155.

214 Eshel Ben-Jacob. Communications personnelles. 1996.

215 M. J. C. Waller. Communications personnelles. 1995-1997 ; M. J. C. Waller. « Darwinism and the Enemy Within ». Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems 18:3 (1995), pages 217-229.

216 Eshel Ben-Jacob. Communication personnelle. 7 septembre 1999.

217 J. A. Shapiro. « Genome Organization, Natural Genetic Engineering and Adaptative Mutation ». Trends in Genetics, pages 98-104 ; J. A. Shapiro. « Natural Genetic Engineering in Evolution ». Genetica, pages 99-111 ; J. A. Shapiro. « Natural Genetic Engineering of the Bacterial Genome ». Current Opinion in Genetics and Development, pages 845-848.

218 Eshel Ben-Jacob. « Bacterial Wisdom, Gödel's Theorem and Creative Genomic Webs ». Physica A, page 70 ; Eshel Ben-Jacob. Communication personnelle. 20 février 1999.

219 Eshel Ben-Jacob. « Bacterial Wisdom, Gödel's Theorem and Creative Genomic Webs ». Physica A, page 79.

220 D. R. Smith et M. Dworkin. « Territorial Interactions between Two Myxococcus Species ». Journal of Bacteriology, février 1994, pages 1201-1205.

|

|